Expanding to Motion/Video and Registering Your Copyright Online

I'm pleased to be returning to the blog and before I get started, I thought I'd share a few images from the last few weeks that have kept me busy in Washington, D.C.

On assignment covering the President, we left The White House in the motorcade where the President was to play golf. Here's the view from the press position out of the sunroof of "Press 2" awaiting the President's departure from the White House, cameras at the ready:

Here's the network TV cameraman in "Press 1" riding in front of "Press 2" documenting the motorcade rolling:

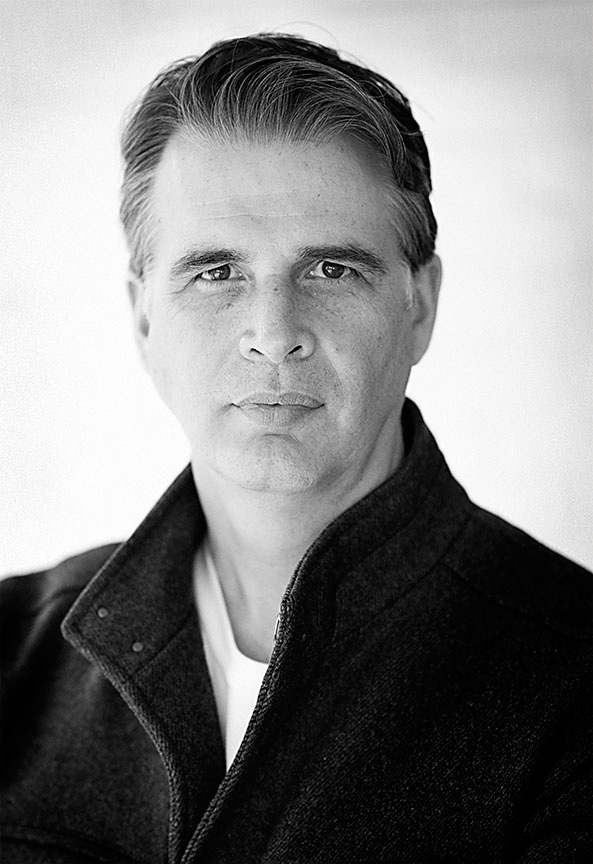

When Army Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl was released and his parents appeared with the President in the Rose Garden, I made the standard image from the front:

Taking a step back and to the side is a way to take a different look at the situation, and also gives you a feeling for the scene.

However, it's important to be not only thinking a few steps ahead to anticipate what's going to happen, but also put yourself in a position to capture something different. While I knew there would likely be a hug, those can often be awkward, and they don't always happen. Instead, I knew they would recess back to the Oval Office, and I thought that would be a better image.

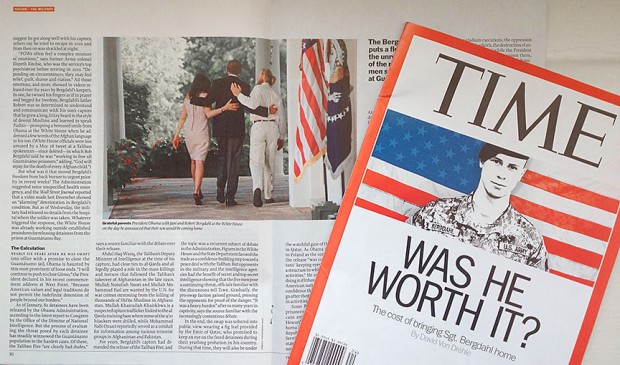

Apparently, Time Magazine liked my image as well:

Next up was a Congressional hearing into the IRS' targeting of conservative groups, where the Commissioner of the IRS was engaged in heated exchanges with the Members of Congress:

And then there was the comedian Gabriel Iglesias promoting his motion picture release - The Fluffy Movie - at the local legendary Ben's Chili Bowl.

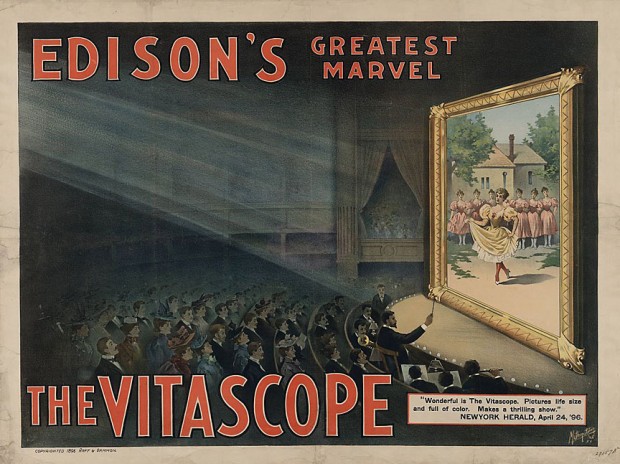

Which brings me to the first half of the important message for this blog post - making motion pictures. So many still photographers today are either experimenting with, or being asked by clients, to produce a project that is motion, and not still photography. Now, we use the term "motion" (or are encouraging you to not use "video") because calling motion "video" is akin to calling your mobile phone a "cellular" phone. So, we use "motion" and encourage you to do so too. It's not like it's a new characterization - the phrase "motion picture" has been around since Thomas Edison invented "motion picture machines" in the 1890's (or arguably Louis Lumiere in 1895). "Video" came into parlance many decades after that, and refers more to the format of recording onto magnetic tape, and, well, you know that we're not doing that anymore. So, let's return to "motion."

The challenge in producing motion projects is that while the concepts of framing, getting the exposure right, and lighting are similar, there is so much more to learn. Moving the camera, or the subjects moving within the static frame, are far more complicated than you think, and the issue of story-telling in a succinct way becomes paramount. Then, as if that's not enough to worry about, anyone who's ever produced a motion project will tell you, a entire production can be ruined by bad audio.

Vincent Laforet is winding down a lecture series - Directing Motion – that has travelled the country, that really shows you exactly how to deal with storytelling, framing, and motion within the frame. Here's a teaser that is for the lecture series (you should go to one of the few remaining dates if you can) but if you can't, the videos that break down how to understand motion and direct it, using some of the most well known films of all time.

Exposure and lighting are very similar to issues that still photographers face, and what I will say about the importance of good audio - it's like backing up your work. There are two types of people in this world, those that have had a hard drive crash, and those that will. You don't get religion on backing up until you've lost a bunch of your work, and you won't get religion on bad audio until your project has had to suffer through it (or fail altogether because of it).

It's very important to ascertain what the client expects from you for a motion project. We go through, in great detail, the vast majority of things that about 98% of still photographers that are transitioning into motion would ever need to worry about in my book, MORE Best Business Practices for Photographers. Among the many considerations are: Are you just producing the raw content, or do you have to deliver a finished edited package ready for the viewer? Are you developing the storyline or does the client already have one they want you to bring to life? How many locations will you be working in? Do you need actors to be hired? Do we need music for the project? These are just a few of the many questions you'll want to ask. Just as a client will say to you "I want a portrait of my CEO along the lines of the one you did on your websiteâ¦" it can answer a number of questions if you ask the client if they have any videos they've seen that they want you to emulate.

As you begin to get calls for motion, you may well be able to do the project as a "one man band" operation. Just like the musician, if you're just playing the guitar but were able to start the drum machine first and then sing as well, you've got about three instruments going. You can light it and then frame the visuals, and if you're lucky and have a wireless microphone on your subject(s) capturing audio, but if it gets more complicated than that, you're in trouble - and more complicated means that people are moving in and out of the frame, for example. When was the last time a great musician was able to simultaneously – in real time – play all the instruments? Right, never. At some point, you need to know when to hire in members of a crew that can properly do the different aspects of a production that can then result in a great finished motion project.

The first crew member to bring in is usually an audio technician, and then adding in a stylist, lighting director, or hair and makeup rounds out your crew. After you're done, even though you may be great at using Final Cut Pro or Adobe Premiere, having someone do your graphics and animation in Apple's Motion or Adobe's After Effects will give you much better results. Once you get beyond one or two additional people, your title is now Director and/or Producer.

The going rate for a two person crew for 8 hours is between about $1,250 and $1,500. This includes a basic motion camera, and a basic two-light setup and two channels of audio. The finished deliverable is the raw footage, without editing. Crew beyond that is - and we're ball-parking here - about $50/hr for, say, a camera operator, focus-puller, and so on. Will you need all these additional crew members? In the beginning, likely not, but eventually, you may well. Asking lots of questions helps you understand what the client is expecting.

Among the worst problems is if you shoot in the 4:3 aspect ration (which is the standard for most older television sets) when the client wants 16:9, which is more of a current standard. But, beyond that, there's what "flavor" of HD - 1080i or 1080p, 720p, and so on. Is your client US based, and thus, wants NTSC, or based in another country where PAL is the standard? What about where the piece will be played? If it's destined for televisions, there are different framing considerations for "TV safe" areas, but if it's destined for a web video, then what you capture is almost always what you'll see. But then again, not always! Ask your client lots of smart questions, and as the project grows, don't be afraid to ask for help in the form of more crew that will deliver the project properly, and garner you a reputation for quality work that will earn you repeat business. Keep in mind - where you might be thinking you need to come in at a low price to get the project, in all likelihood this client has hired motion producers before, and if they are used to a $10k budget, and you come in at $4500, it's not that they will hire you because you're cheaper than half the price, but it will be evident that you are not estimating to cover all the things they are expecting, and clearly your low budget figure only evidences that you're not qualified to do the project properly. One of the most important questions you can ask a prospective client is "what budget are you trying to work within?"

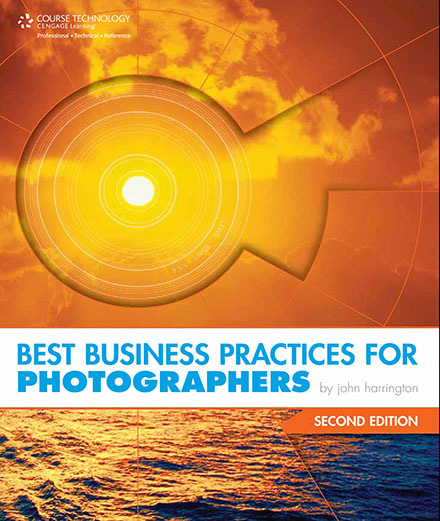

Back in the still photography arena, we've registered well over a hundred different copyright registrations and in my first book, Best Business Practices for Photographers, I detailed exactly how we did that using the printed Form VA along with a DVD of images. While that system still works and is acceptable, In my latest book, MORE Best Business Practices for Photographers, I go into detail as to exactly how to do it using the online registration system, the Electronic Copyright Office, or eCO. My goal was to demonstrate that you could register many thousands of images in an hour or less, and if you're doing the registrations monthly, that works out to be an hour a month.

You've no doubt had a number of people tell you how important it is to register your work, but you've just been daunted by the process, so I won't go into the "why" here, just the how. The key thing is to not worry right now about the mountain of images you've produced in the distant past, but work on what you've produced recently and start a system moving forward to register methodically. Once you've done a few, it's easy to then go backwards and register past works.

As I prepared the chapter on using the eCO I was fortunate to be able to have one of the members of the Copyright Office's legal team as well as the Assistant Chief of the Visual Arts Division of the Copyright Office look over the chapter, and the Assistant Chief also reviewed the video.

This is the entire video, and it should probably be behind a paywall somewhere, but it's not. While the book goes into detail on various uses of the eCO, the video does not require the book at all. The link to the spreadsheet is here that is a part of this process. This is the system to use for works that have been published. That said, once you watch the video, you can see how it could just as well be used to register unpublished works too.

For over two decades, John Harrington, an award-winning photographer and best-selling author has covered the world of politics, traveled the globe, and run a successful business requiring the non creative but essential skills that make a business function.

John grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area before moving to Washington, DC in the mid-80s for college. A 2007 recipient of the United Nations’ Leadership Award in the field of photography, his work has appeared in Time, Newsweek and Rolling Stone. His commercial clients have included Coca-Cola, SiriusXM Satellite Radio, Lockheed Martin, and the National Geographic Society.

John has produced three commissioned books for the Smithsonian and the second edition of his book, Best Business Practices for Photographers, remains a bestseller. In 2010, a retrospective of his first 20 years in the profession – Photographs from the Edge of Reality, was released and revisits highlights of his career. In June of 2014, his second book on the photography business, MORE Best Business Practices for Photographers was released.

John currently sits on the national boards of the National Press Photographers Association, American Society of Media Photographers, and White House News Photographers Association where he is also President Emeritus after having served two terms.

One of the best Guest Blog posts ever, thanks.

Excellent piece today. Interesting back story on recent work and great advice about how to approach motion projects (or any assignment, for that matter!). Thanks John.

So I suppose “dialing” my cellular (oops, scratch that) make it mobile phone is also out of the question! Thanks for the guidance, I have to keep reminding myself that I’m from the previous century! Great article! (oops again, make it Great Blog!)

“. . . we left The White House in the motorcade where the President was to play golf.” Haha, he’s already up to 175 rounds!