Who doesn’t like a good travel story, one that has a meaningful moral? Who doesn’t like to see captivating travel photographs—images that motivate and inspire? And who does not like going behind-the-scenes to learn what went into the making of a travel photograph?

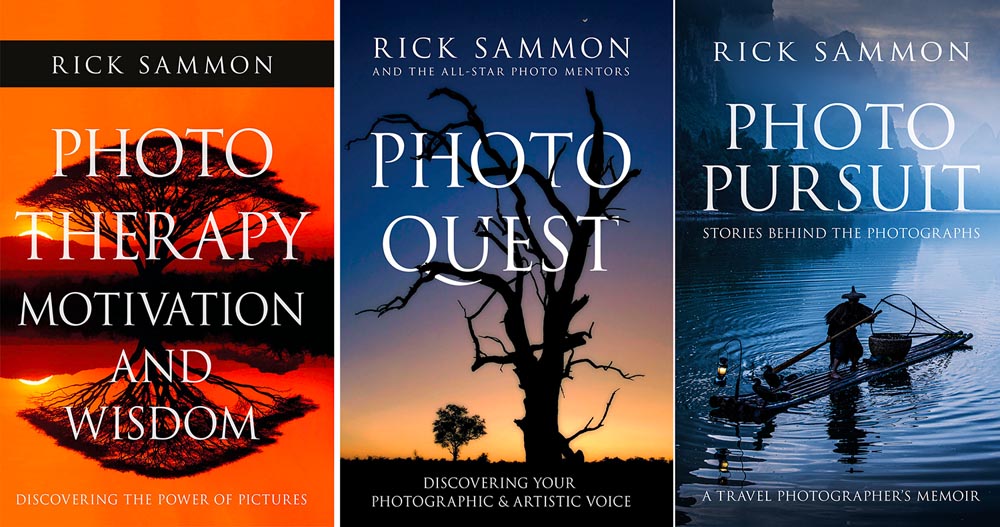

That is where my 42nd book, Photo Pursuit: Stories Behind the Photographs – a travel photographer’s memoir (a Kindle book readable on all devices, including IOS devices, with the free Kindle reader) is all about.

In this guest blog post (thank you Scott and Brad), I’ll share three of my favorite Stories from the book, which features 38 Stories along with more than 40 full-color photographs.

But first, a bit about the book.

Through my storytelling for each photograph (some of my favorites from my travels to more than 100 countries), you will learn about important photographic techniques that you can apply to your own photographs—when traveling to faraway places or when photographing close to home. In fact, this info-packed book offers all the practical photo tip, tricks, and techniques that you can use to make pro-quality images.

And speaking of images, this book is best viewed on a full-color device for maximum photo quality.

Woven into my stories are camera settings, gear choices, and other important photographic techniques.

In reading this book, you will also learn something about the different locations and what it’s like photographing in those locales, which can help you make better photographs in similar situations.

So, in effect, this book is also a travelogue. You’ll get a taste of what it’s like photographing in Antarctica, Africa, Botswana, China, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, Papua New Guinea, Myanmar, Iceland, Italy, Lake Baikal, The High Arctic, Provence, and Alaska, to name just a few fascinating places in which I have worked.

Each of the 38 chapters is a story, and each story is accompanied by Morals of the Story. These takeaways are designed to reinforce the message of the story. In fact, in writing each story, I wrote the Morals first so I could weave in my most important tips and advice in an interesting storytelling fashion.

Virtually all of the photographs in this book were taken on my photo workshops or photo tours. I mention this because joining a photo workshop or tour is a wonderful way to see the world and to get photographs that perhaps you could not get on your own.

Again, this is a Kindle-only book. It is my first ebook-only book, and I am actually surprised at how easy it is to read and how good the images look on my iPhone and iPad.

This book was fun and rewarding to write. And now, perhaps because I am 71 years old and wrote this book during the pandemic of 2020/2021, this book has special meaning. Photo Pursuit is a recap of some of my favorite travels with my wife Susan Sammon, making the book a travel photographer’s memoir. Authors seem to put the most effort, passion, and love into memoirs.

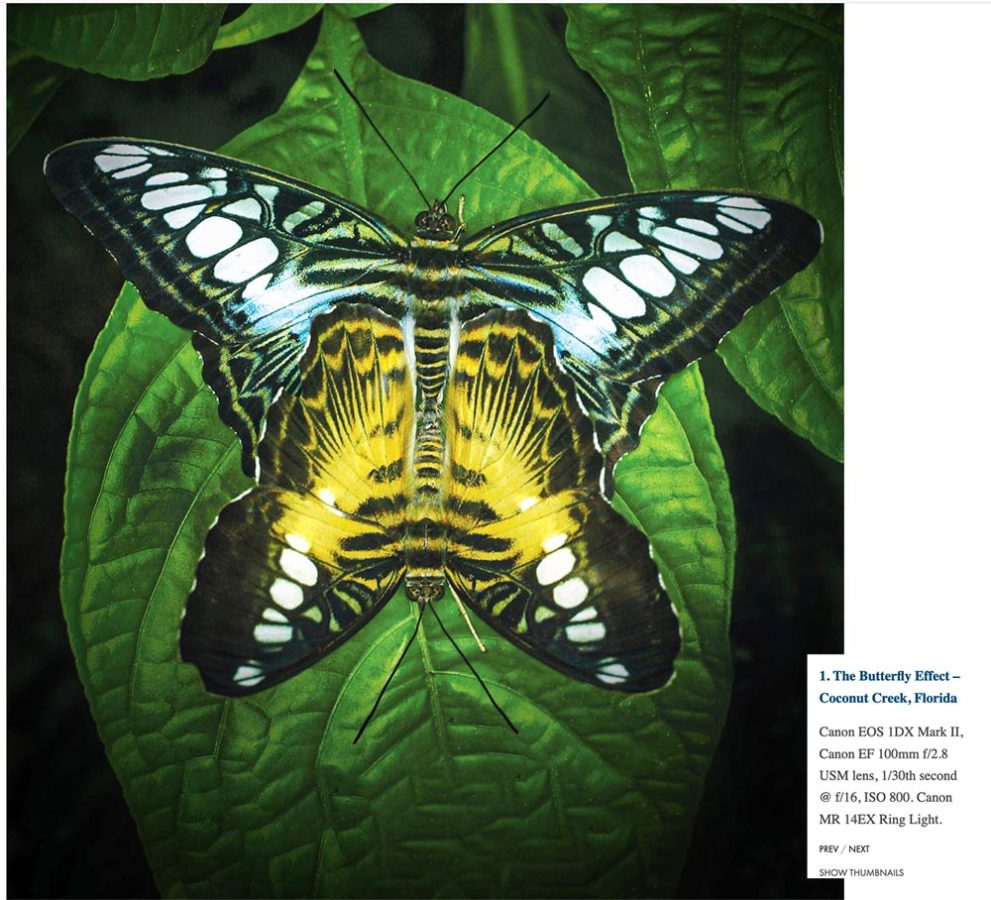

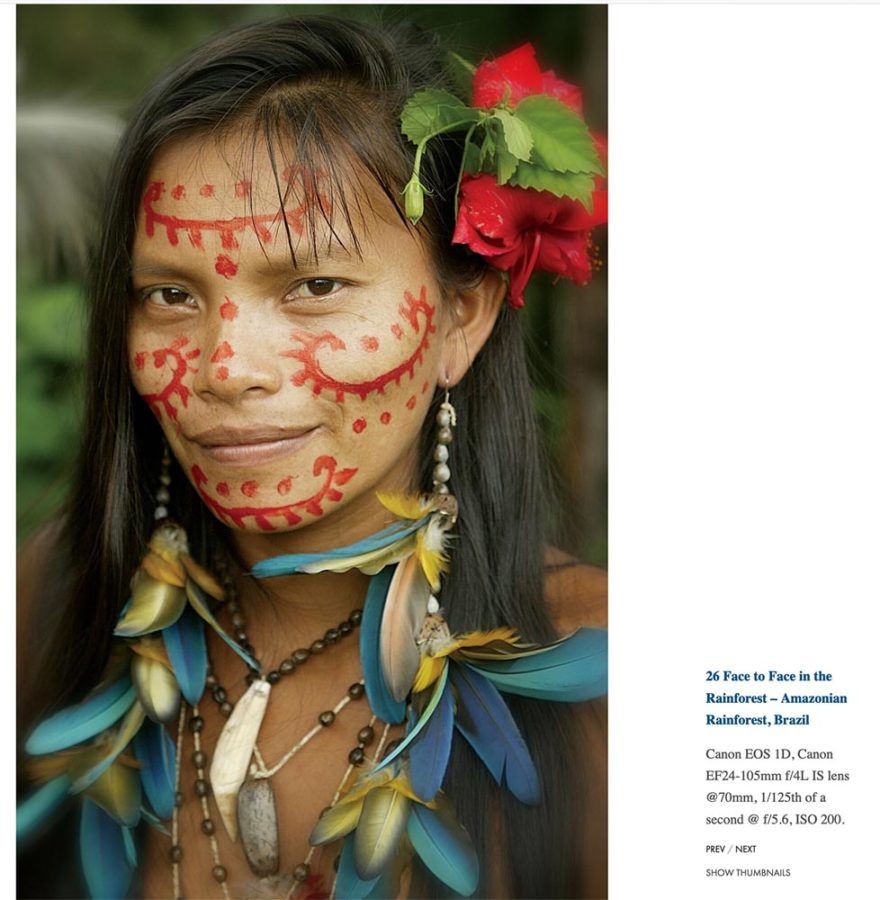

The Appendix for the book features all the tech info for each photo. In addition to finding the EXIF date in the book, I set up a Gallery called Photo Pursuit, on my web set so readers can see each photograph along with the info.

For readers of this book, I think you will find the exposure and location information useful if you find yourself in a similar situation.

Photo Pursuit is the third book in my recent “Photo” series. Photo Therapy was the first and Photo Quest was the second. You’ll find info on all my recent book on this page: https://ricksammon.com/ricks-books

Okay, here are the three Stories from my book. Enjoy!

The Butterfly Effect

Coconut Creek, Florida

The Story

The year is 2002.

Before getting to the story, for those of you who don’t know about the “butterfly effect,” here you go.

Basically, the concept is that even small vibrations in one part of the world can change vibrations, such as the weather, in other parts of the world. On a more personal level, the “butterfly effect” means that even small changes in our thinking, energy, and actions can lead to significant changes in our lives.

I am not sure about the first example, but I can vouch for the second. Here’s the story:

In Story 4: Monarch Migration in this book, I share my experience of photographing a kaleidoscope (a butterfly gathering) of millions of monarch butterflies during their overwinter stay in the remote mountaintops of Michoacán, Mexico.

The photograph in this story, taken the previous year at Butterfly World in Coconut Creek, Florida, of two clippers mating, launched my passion for photographing butterflies, which eventually landed me in Mexico.

To me, the photograph captures a beautiful, colorful, and touching scene of a magic moment in nature: the start of a next generation of butterflies, which begins when the female lays her eggs and ends when she dies shortly thereafter.

In effect, my mating clippers photograph had seven main “butterfly effects”:

First: In 2002, while showing my butterfly photographs (including my mating clipper shot) to the head of the Canon Explorers of Light program, Dave Metz, I learned that he was in a time crunch for an exhibit of large photographs at the Canon booth at the Photo Plus Expo show, an international gathering of photographic manufacturers and photographers in New York City.

Dave liked my photographs, and rather than having a traditional exhibit of photographs from several Canon Explorers of Light, which would have been difficult to coordinate, Dave asked me if I’d like to have the entire 16-print exhibit.

Of course, I said, “Yes!”

Getting the exhibit was the first effect.

Second: Dave then asked me if I’d like to give a talk about my butterfly pictures at the Canon booth on the main stage at the show.

Another resounding, “Yes!”

Getting the invitation to speak at the Canon booth was the second effect.

Third: I gave my presentation at the show.

After my talk, a woman came up to me and said, “Hi, I loved your work. And I love your enthusiasm for photographing butterflies. I’m Lena Tabori, owner of Welcome Books. We’d love to do a book on butterflies with you.”

Getting the book contract for Flying Flowers was the third effect.

Fourth: Shortly after the show, Dave called and invited me into the prestigious Canon Explorers of Light program, which is comprised of some of the top professional photographers in the world.

This time, I not only said, “Yes!” I said, “Thank you so much Dave. It’s an honor and a privilege.”

Today, in 2021, I am still a Canon Explorer of Light, which has generated many opportunities and stories, some of which have been life changing.

Being invited into the program was the fourth effect.

Five: My passion for photographing butterflies led me to Michoacán, Mexico, where I was amongst millions of butterflies, and which was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Traveling to Mexico was the fifth effect.

Six: Before the publication of Flying Flowers, my wife Susan asked me to exhibit two of my butterfly photographs in a local art show. At first, I said I was too busy, but Susan used the magic word, “Please,” so I agreed.

In reading a review of the show in our local paper, I was pleased to see what the writer said about my photographs:

For their sumptuous textures and colors, and the sheer wonder these finely detailed photographs of butterflies awaken in us, I think Rick Sammon’s photographs are marvels.

—Maria Morris Hambourg, Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Who knew Maria lived in our area and would attend the show? I used the quote, with Maria’s permission, on the back cover of the book and in the promotion of the book. I can’t tell you how much that helped sales.

The local exhibit was the sixth effect.

Seven: After learning about my book, another publisher contacted me about doing a series of butterfly note cards and a calendar.

The resulting butterfly calendar and notes cards were the seventh effect.

There are more “butterfly effects” from my mating clipper photograph, such as me writing this chapter and you reading this chapter, and perhaps you being inspired to make some of your own wonderful butterfly photographs—and you thinking about the “butterfly effect.”

For those interested in photo techniques, here’s how I made my mating clippers photograph: I used a technique called daylight fill-in flash. It gives photographers a way to balance the light from the flash (speedlite) with the available light.

The goal of a daylight fill-in flash photograph is to make it look as natural as possible, without strong, unnatural shadows created by an on-camera or hot-shoe flash.

I was photographing these butterflies with my 100mm lens and ring light, a device that fits over a lens that has two rounded tubes that can produce soft and even lighting, or ratio lighting if you adjust or turn off one of the tubes.

After several test shots, during which I increased or decreased the light output of the ring light (using the +/– exposure compensation setting) or increased or decreased my shutter speed (to let more or less light into the camera), I was able to get a fairly balanced image.

You can learn more about daylight fill-in flash by doing a Google search: Rick Sammon, daylight fill-in flash.

The Morals of the Story

- Never underestimate the power and importance of one of your photographs, as well as your actions.

- Always be on the lookout for business opportunities.

- Always do your best, because you never know who is watching.

- Master daylight fill-in flash photography.

The Safety of Reminiscence

Snow Hill Island, Antarctica

The Story

The year is 2008.

Marco Polo, the Italian explorer who traveled the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295, had many adventures. In his writings, he summed up some of these adventures: “An adventure is misery and discomfort, relived in the safety of reminiscence.”

Basically, Marco Polo was saying that hardships in the field are often reveled in, even laughed at, once we are back home.

With this thought in mind, here is my favorite “safety of reminiscence” story.

It is December 2008. Our expedition ship has just left port in Ushuaia, Argentina, on its way to Snow Hill Island in Antarctica. This is to be a very special expedition, with the goal of seeing and photographing emperor penguins, the tallest (they can reach a height of almost 40 inches) and heaviest (they can weigh up to 50 pounds) penguins in the world. They, like the slightly smaller king penguins, are very photogenic and majestic.

I am the photo coach on the expedition, hired to help guests get great shots and process their images on their laptops.

This expedition is relatively short: three days to get to Antarctica (about average for a ship), four days of observing and photographing in Antarctica, and then three days back to Ushuaia. A total of 10 days, not counting the two days of travel each way from New York to Ushuaia.

Everything is going according to plan, the seas are calm and the weather is wonderfully warm, as it usually is during the summer months.

The passengers cannot contain their excitement. Some of them have saved a lifetime for this adventure. I am thrilled too…until we arrive on-site.

As soon as we arrive at Snow Hill Island, the weather turns bad: the sky is severely overcast, and visibility is limited. It is so bad that the two Russian-made helicopters (on our Russian-made ice breaker) that would transport us from the ship to the emperor penguin colony cannot fly.

It’s Day 1 on-site. Rather than seeing penguins, the guests see slide shows presented by the on-board naturalists and experts, including myself. Basically, we are filling/killing time until the weather clears.

Conditions on Day 2 are no better: it is snowing heavily. Again, the helicopters cannot fly. More slide shows. More food. More slide shows. More food.

It is still snowing on Day 3. The mood on the ship is not good.

Shortly after breakfast, things get worse: about half of the ship’s passengers, including the ship’s doctor and me, come down with the highly contagious Norwalk virus. If you have had the virus, you know how painful it can be—it’s the feeling you get when you combine food poisoning with the sensation of having a pitchfork stuck in your gut.

Those of us who have the virus are quarantined to our cabins. The crew brings us our meals. The other passengers are able to get off the ship, which is moored, bow first, in the ice. There are a few penguins around the ship, providing the guests with an opportunity to get some pictures.

In my cabin, I think I am going to die. It is that bad.

Fortunately, the virus symptoms only last between 12 and 48 hours, and I, like most of the passengers, begin to feel better on our last scheduled day at Snow Hill Island.

Good news brightens Day 4: the sky is clear. The captain comes on the loudspeakers and says that the helicopters are ready to fly! The choppers make several trips from the ship to the island.

When we land on the island, we are about a half-mile from the penguin colony. Now, feeling exhausted from being sick, we have to walk over the snow and ice, wearing our heavy parkas and life jackets (because it is possible to fall through the ice), and carrying all our camera gear in our backpacks. Not fun, or as the saying goes: “It’s not easy having fun.”

When I arrive at the photo location, I am awestruck by the sight of the emperor penguin colony. There are hundreds of the animals, adults and chicks, surrounded by a dramatic Antarctic landscape.

We only have an hour or so to see and photograph these majestic birds, so as usual, I set a goal to get a specific type of photograph. Rather than using the “spray and pray” approach, often called the “machine gun” approach, I use a targeted approach, also known as the “bow and arrow” approach. Basically, I am looking for a National Geographic style cover-type shot: mommy, daddy, and chick.

Scanning the colony, I spot the shot I am looking for: two parents with their chick (emperor and king penguins only lay one egg after mating; all other penguin species lay two eggs at a time).

I unzip my waterproof camera backpack and take out my camera. Because it is snowing lightly, I cover the camera with a plastic camera cover, an accessory I always keep with me for just this type of situation.

I get down on my belly, compose the scene without a cluttered-with-penguins background, and shoot. (As it turns out, it’s the only “keeper” I get from the entire expedition.)

Shortly thereafter, I hear the expedition leader announce that it is time to head back to the helicopters. I pack up my gear and, still feeling the effects of the virus, slowly trudge back to the choppers.

Was the one shot worth it? Sure…in the safety of reminiscence. I get more than a few laughs when I share this story, which I tell with a smile on my face because it was indeed an unforgettable adventure.

P.S. During this adventure, I had the honor of meeting Jonathan and Angela Scott, who were guests on the ship. Jonathan, who I had seen on television when he hosted Big Cat Diaries, is known as the Big Cat Man and this dynamic duo is known collectively as the Big Cat People.

We kept in contact and became dear friends. Seven years after our Antarctica adventure, Susan and I were in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya, photographing with Jonathan and Angie. It was an experience that, as my dad would say, “we would not have missed for the world.”

The Moral of the Story

- Sometimes, one great shot is better than lots of snapshots.

- Keep in mind that, when travelling, things don’t always go according to plan.

- Shoot at eye level, and don’t be afraid to lie in penguin poop.

- You never know who you might meet when traveling.

On the Run

Provence, France

The Story

The year is 2013.

It’s late afternoon on the first day of my Provence, France, workshop, which I am leading with a local photo expert Patrice Aguilar. This is our second workshop together; we conducted the same workshop a year before. It was so successful and so much fun that we have to do it again.

Our group consists of ten photo workshop participants who have come from around the world to capture the striking white Camargue horses in action.

Our goal on this morning’s photo shoot is to get photographs of the Camargue horses, illuminated by the beautiful early morning light and running toward us through the water at top speed.

Wearing waterproof boots, we are standing about 300 yards offshore in calf-deep brackish water, our feet sinking slightly into the mud. We are waiting for the action to begin.

Each photographer has one camera body and two lenses, because that is what Patrice and I recommended the night before at our workshop welcome dinner.

One lens (either a telephoto zoom or a wide-to-medium zoom) is mounted on one camera (with a camera strap), and the other lens is tucked in a photo jacket or vest pocket.

We also have our smart phones for behind-the-scenes shots and videos.

Everyone also has a plastic camera cover to protect the cameras from the splashes that Patrice warned us about.

Twelve horses are standing on the shore. Four Provence “cowboys and cowgirls” are keeping the animals calm and in position. These expert horse handlers, as Patrice discussed, will guide the horses toward our group, and at the same time, try to stay out of our images. That is not an easy task when all the horses are running at the same time in basically the same direction.

The sun is at our backs and will perfectly illuminate the horse’s faces as they come toward us. Our position is no accident. Patrice has conducted many workshops on this pond and knows exactly the best position from which to shoot at different times of the day for the best possible shots. He understands light.

We are almost ready for the first run. Patrice gives us stern instructions: Divide into two groups: five and five. Stand in a straight line. Stay close together. Leave an opening of about 8 to 10 feet between the two groups. That way, when the horses run toward us, he says, they can go around the group or through the opening between the two groups.

I suggest to the photographers that they set a goal: go for either group shots or single-horse shots. I go on to say that because the horses will do several runs, everyone will have an opportunity to get both types of shots.

I also make an exposure suggestion: set your exposure compensation to –1 EV to start, because the dark water around the light horses might fool the camera’s exposure meter into thinking the scene is darker than it actually is, overexposing the horses. I explain that in Photoshop and Lightroom, it’s easier to pull out detail from the shadows than it is to rescue overexposed highlights.

We are all ready to go.

Because I took group shots of these horses in the same location the year before, I decide to go for a single horse shot.

I have a specific goal in mind: I want to get a photograph that shows the power and beauty of a Camargue horse. Photographing from a low angle will accomplish that goal—if the horse is close and running fast.

I am standing at the outer edge of one of the groups. Knowing that I cannot crouch down in the water, I decide to hold my camera off to my side, about a foot off the water.

Not knowing exactly where a horse might be, I set my zoom to a medium-wide setting of 40mm. And, because a horse might be moving erratically, I estimate where the animal might be and set my focus to 10 feet. At f/8, I know I’ll have enough depth of field to get the entire animal in focus.

I also set my camera to the highest frame rate to capture subtle differences in the horse’s movement. My exposure mode is set to aperture priority.

Holding my camera in position, and after asking all the workshop participants if they are ready, I give Patrice the okay to start the shoot.

Patrice gives the signal. They are off!

The horses, indeed, run toward us at top speed. Shutters begin clicking, but I wait for a horse to get close for my intended shot.

As one magnificent horse approaches, I aim my camera in the general direction, depress the shutter release button and take about 20 frames.

The shot you see here is the one shot in which there are no other horses or riders in the frame, and in which no part of the horse is cut off. It’s also the only image with a nice background. What’s more, the photograph illustrates an important point: you don’t always need to be looking through the camera’s viewfinder or at the camera’s LCD monitor to get a good shot.

That’s the good news part of the story.

Here’s the bad news part of the story. One of the workshop participants decides to change lenses before the action begins, and accidentally drops her camera into the water. The good news part of that bad news story is that another participant has an extra camera and lens that she can borrow for the other workshop shoots.

Flashback: On my first trip to Provence, we also had a mishap. A woman standing at one end of the line, as directed, moved away from the line as the horses approached. She got so excited about getting the shot that she forgot to follow Patrice’s advice to stay shoulder-to-shoulder in the line. A horse got confused by the gap and knocked her—camera, iPhone, and all—into the water. The horse also stepped on her ankle, which resulted in a trip to the local hospital.

Fortunately, she was okay, but her camera, of course, was totaled.

Getting back to this day’s shoot, Patrice and I direct the local riders to make five more runs with the horses, ensuring that everyone on the workshop gets the shots they want to make. As we wrap up, everyone is on an adrenaline high. We end the day at a local café enjoying fresh seafood and wine and sharing impressions of our amazing group experience.

P.S. In reading this chapter, Susan reminded me of a very unexpected encounter. On our first early morning shoot, we were attacked by hundreds, maybe thousands, of hungry mosquitoes! The attack was so intense that we had to abandon the shoot and make a trip to a local store to pick up insect repellent for our group. Those cans of insect repellent saved the day—and the shoot!

The Morals of the Story

- You don’t always need to be looking through your camera’s viewfinder (or at the LCD monitor) to get a good shot.

- Autofocus is not always the best choice.

- Follow the advice of your guide or photo workshop leader.

- Note the direction of light and make sure it is illuminating the subject in the best and most flattering manner.

- Think about the feeling you want your photograph and subject to convey in your final image.

- Be prepared with the right clothing.

- Protect your camera from the elements.

- Choose your lens or lenses very carefully.

- Anticipate the action.

- Give credit where credit is due, as I do in this story to Patrice.

Rick Sammon is a long-time friend of KelbyOne and has almost 30 classes on KelbyOne.com. You can see more from Rick at RickSammon.com, and keep up with him on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Pinterest.

1 comment