Cultivating a Photographic Vision

First off, I would like to thank Scott and Brad for this opportunity, it’s an honor to be a guest on here. I also want to thank Scott for hiring me back in 2013 as an assistant to help with remote cameras at an Atlanta Falcons game. I had been a Sports Illustrated assistant for several years before helping Scott, but that opportunity led to me shooting an entire season for the Falcons, which in turn led to many other opportunities (including being featured by Instagram for my Falcons work).

For this post, I’ve decided to write about having a vision for photography. It may sound grand and vague and only reserved for fine art photographers, but it’s something I think photographers from many disciplines, if not all, should aim for.

It can be hard to define what having a vision really means. It’s a lot like art itself; it can be easily recognized, but very difficult to put into exacting words.

Talking to Chris Aluka Berry, a good friend and a remarkable photographer, we discussed what having a vision meant, and I think he summed it up well:

It becomes apparent that a photographer has a vision when you can see the photographer in the work. If a portrait captures the essence of a person, then the photographer’s body of work should capture the essence of what he or she is trying to say.

Chris Aluka Berry

But how does one go about doing something like this? I don’t pretend to be an expert on this topic or be able to give a step-by-step guide on obtaining a vision for one’s photography, but I am offering some experiences and what has guided me towards a personal vision of how I see.

A Bit About Me

It was about 15 years ago when I first remember hearing the words “vision” in this context. Barely a photographer myself, I was intrigued and wanted to begin working on my own. It was 2004 and I was attending the Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar, an event that attracted young and old, seasoned veterans to rookies like myself.

Several of the speakers mentioned finding and following your personal vision. I had an idea, but I really didn’t know what this meant. But I wanted it. I wanted to feel like all of my work came from a place deep inside, guiding me to make photos that were truly saying something.

I had been shooting professionally for a couple of years by this point. In 2001, I took my first journalism job as a reporter for The Moultrie Observer in South Georgia, a sleepy town with a magnificent courthouse and a downtown surrounded by what seemed like endless miles of cotton fields and pine trees.

Part of a reporter’s job at many small newspapers is to take photos to accompany his or her stories, and working at the Observer was no exception. I was one of two reporters — and though we had a staff photographer, I couldn’t count on him covering all of my stories because of the sheer volume of work he was responsible for.

But this turned out to be one of the biggest blessings of my life. I fell head over heels in love for photography and knew that capturing images would be my path. By 2004 when I was attending the Seminar, I had started working at another small town newspaper — but this time as a staff photographer. My dream had arrived.

This vision these photographers spoke of was now the goal, but it still seemed like something unobtainable. I was more concerned with making sure my photographs were in focus and exposed decently than with creating images that conveyed something larger.

I just wanted photos on the front page — so people would put clips on the fridge door. It was an obsession to make good photographs — I lived for it, it felt like everything was on the line for every shoot. I demanded that I get better, that I figure out how to make photographs that mattered. I wanted my photographs to make people feel.

Shooting For Yourself

One of the most valuable pieces of advice I’ve gotten is to always shoot for yourself. I learned this in the APhotoADay community, an early email listserv started by Melissa Lyttle that served as an online meeting place for (mainly) photojournalists looking to improve and meet others in the field.

The idea was simple — share one per day with the group and get feedback on your work. The comments were sincere, which was at times uplifting and other times brutally honest (like, “you really wasted opportunity and access here to come away with something.”). But then again, no one ever got really, really good at something by being told how amazing they were.

A lot of us, like myself, were photographers at small-town newspapers and didn’t have a lot of resources for feedback. I was the only photographer at my paper (The Griffin (Ga.) Daily News) and I had no photo editor or art director. If I wanted advice on how to approach certain assignments, for example, I had to reach out to someone. Many times, that meant emailing or calling photographers are larger newspapers, like the nearby Columbus Ledger-Enquirer or the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The message from many APaD members was simple: make sure you take at least one photo for yourself on every assignment. It didn’t have to be for publication, just something that I wanted to shoot. This may sound very simple, but it can be challenging when assignments include city council meetings and pet of the week. And when days typically served up 3-4 assignments, it was easy to get burned out and lose that creative spark. This is why shooting images just for me was vitally important.

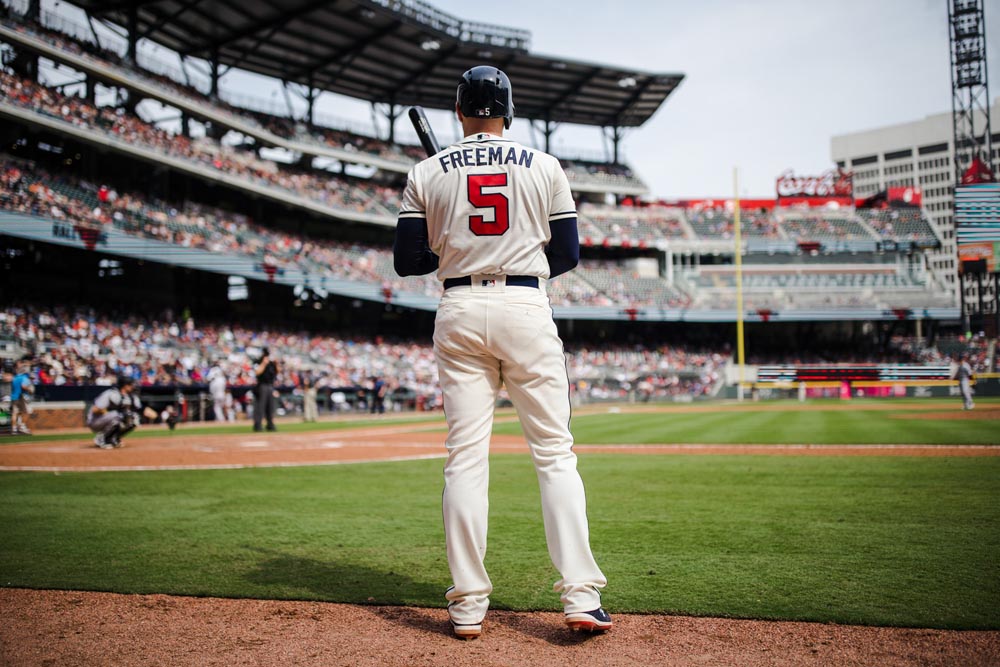

While I’m no longer a staff newspaper photographer, I still try to do this for nearly every shoot, whether it’s covering a Braves game, an SEC showdown for Sports Illustrated or a portrait for a commercial client. It fulfills that creative need inside and keeps me excited about what I’m doing. The wonderful thing is that these images often get chosen and published over what was planned.

Personal projects are a great way to shoot for yourself, while also building a portfolio. The beauty of personal projects is that they are … well, personal. You get to decide what to shoot, you get to edit, and you get to have the final say. Find what moves you, what stories you want to tell.

They’re also a wonderful way to get work. Whenever I’m meeting with editors at publications like The New York Times or Sports Illustrated and showing my work, they always want to see what personal projects I’m working on. These projects are a great way to see what a photographer’s vision is, what stories they choose to tell, what makes them tick. Several times these projects these projects get commissioned as assignments.

Asking Why

I wanted to hear what other photographers have to say about this topic and how their vision came into focus. Ross Taylor immediately came to mind. Ross, also a former newspaper photographer, is now a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and also runs The Image, Deconstructed (TID), a very insightful blog as well as a workshop for photojournalists. I attended the TID workshop in 2018, where I met Ross for the first time.

Ross is simultaneously intense and extremely empathetic, which explains how he is able to gain access so quickly with subjects in difficult situations. It’s immediately clear that he cares deeply about what he’s doing and has a vision. So I gave him a call to get his thoughts.

For me it (crafting a vision) started with purposeful reflection on a central notion of why I’m doing what I’m doing. It seems simple and reductive, but spending time and sitting with yourself is so important. Spend more time thinking and less time shooting. Why are you pushing the button, why are you making the frame?

Ross Taylor

Ross was talking about approaching photojournalism assignments, but this also applies to many other types of photography. Simply asking yourself, “Why am I here?” and, “What kinds of images do I want to make?” can help reveal a vision.

For me, I want to make images that are more than just the moments they capture, I want them to say something larger and stir the viewer emotionally. Asking myself why I’m shooting, why I care, and why someone else should care helps me boil it down to the essentials.

Creating Lots of Work

And lastly, it’s hard to obtain a vision for photography without shooting tons of photos. Digital photography and cheap recording media has removed the costly barrier of creating. It’s through this process that inspiration and meaning are often found. Recurring themes and motifs will present themselves, many times unconsciously.

It was only after shooting for several years that I started to see themes in my work. I often found myself drawn to objects related to religion and worship, as well as moments that exist on the periphery of events, or just before the main attraction. Like the woman sitting alone in church, children watching an eclipse, or Freddie Freeman on deck to bat (all below).

Having a vision is about having a body of work that is cohesive, so it feels like there’s something invisible tying it all together. I’m not a musician, but I love music dearly and think of my work much like I think a musician would. My projects are songs in an album that I am always trying to perfect, to evolve.

And just like a musician has particular sounds and riffs that are particular to his or her work, we have light and color and composition that brands our work. It’s the same feeling I get when I see work by a photographer I’m familiar with — I recognize that feeling and then immediately know which photographer the work belongs to.

Finding one’s vision is no easy task, but nothing worth having is ever easy. Which is why, in order for this process to take hold, photography has to be something you care deeply about or it will be too easy to quit when your work disappoints you. And it will disappoint you.

For me, photography became an obsession and my lifeblood. Without that need to create, the desire to get these stories out, I never would’ve made it past those first few rolls of film.

Kevin D. Liles is a commercial and documentary photographer living in Atlanta. He is the team photographer for the Atlanta Braves and regularly contributes to Sports Illustrated, The New York Times, the Washington Post, and The Players’ Tribune, among other clients.

You can find him at KevinDLiles.com, and keep up with him on Instagram.