In recent years I have photographed and hiked the Kumano kodo pilgrimage trail sacred to Shugendo Buddhism in Japan. I’ve walked long portions of the Camino de Santiago in Spain with my camera. I’ve taken photos to bring light to the near darkness in Son Doong, the world’s largest cave in Vietnam where fewer people have ventured than have been into space.

As a photography workshop leader, I’ve taught groups of photographers in the United States, France, and many other parts of the world. In the course of my travels when I meet people—and I love to chat with folks along the way—once it becomes known that I am a professional photographer, one question is pretty constant: What kind of photographer are you?

Generally, when folks ask me this question they are looking for a pretty straightforward answer. Sometimes I wish I could tell them “I photograph children for a portrait studio,” “I am an architectural photographer,” “I am a wedding photographer,” “I photograph jewelry,” or something similarly specific.

As I’ll explain later in this blog story, I’ve worked professionally in a number of photographic genres, back at the beginning of my first photography career in the days of analog, film photography.

No knowledge is ever wasted. It’s helpful to have the skillsets from the different photographic niches under my belt, as well as my experiences as a computer programmer, fine-art painter, and a writer. But none of these individually fit what I’ve been doing and what I have regarded as my current profession since the dawn of digital era.

I tell folks who ask that I am a Photographer as Poet. That’s of course the title of this blog story. Stay tuned: in this blog story I’ll tell you what I think being a Photographer as a Poet means, some of the history of how I’ve arrived at this profession and calling, and some words about what it means to have a professional practice as a photographic poet.

I’ve become so enamored of my job title of Photographer as Poet that I had an inkan—a Japanese “chop” or inked stamp that is sometimes used in place of a signature—created with the characters that roughly translate to this phrase. Sometimes I use my inkan to handstamp and decorate my prints, particularly those printed on Japanese washi.

What does it mean to be a “Photographer as Poet” professionally? This is often a follow-up question to “What kind of photographer are you?”

I’ve found that the simplest answer is to say that I photograph whatever I want, and later find a way to make a living with my photos. Of course, this is a vast oversimplification—both on the photography side, and on the “making a living” front—but it gets my point across. Just as a good poet does, I am answering to my calling at the behest of those higher powers that I can access—and not working as a hired gun for commercial interests.

Speaking of poets, the great modernist poet Wallace Stevens had a day job as an insurance executive, and it’s rumored that E.E. Cummings wrote advertising copy using a pseudonym, but mostly poetry is an avocation pretty distinct from commerce.

Similarly to poetry, for me photography is an avocation and a calling, and not a commercial job description. That my work finds a public to help support it is a happy side effect of the work, and not its purpose.

A bit more practically, I am an artist, photographer, and writer—in that order. I have followed my own path and often taken the road less traveled. The three legs of the art, photography, and writing triangle support my avocation as Photographer as Poet.

My writing supports my photography. Ansel Adams, who had an apt aphorism for everything, once said that the most important tool in his camera bag was his pencil and notebook. I agree. When I write about photography in my blog or in my photographic technique books I learn more about photography, and learn to become a better photographer.

Just as my writing supports my photography, my photography supports my art. By this I mean that I am first and foremost an artist. As an artist, the medium that I use for my source material is primarily my photography. For me, the photography is my starting place. My art largely depends on what I do with my photographic source materials after I have copied the photos from my camera to my computer.

Another way of looking at things goes back to the simple idea that if you want to make better photos, stand in front of more interesting things.

Interesting things are all very well and good, and I do find travel, along with the new experiences it engenders, inspirational. Of course, many things are inspirational, including hiking in the wilderness, listening to music, people one meets, and some spiritual and religious experiences. So I find it helpful to rephrase this advice: If you want to make better photos, stand in front of more interesting things. If you want to make really better imagery, become a more interesting person.

So we now have three axes. First, find interesting things to photograph. This is as good a place as any to strongly note that interesting things abound all around us, and can as easily be found near at home as far abroad. You don’t need to travel to make great photos.

Next, regard photography and the making of photos as a kind of quest, or spiritual journey. It truly is the case that the best images are made when we tap deeply into the well that is our truest self, and I feel most like the Photographer as Poet of my aspirations when I let go, and am guided by forces that are beyond my limited conscious understanding of the universe.

The model of the quest is also significant: One is given a quest and must accept it whole-heartedly. But often there are side-adventures along the way, and while on a quest one should always be open to taking the adventures that are given, even if they were not seemingly the original intent of the quest.

The third axis is the practical, and this spans a wide range of topics and materials, including the technical side of photography, post-production using Photoshop and other tools, marketing one’s work to insure that the work sees the “light of day,” and understanding the technical, art historical, and contemporary context of the work one is creating.

To summarize: Becoming a Photographer as Poet means leading an interesting life and finding interesting things, whether they are near or far. This should be done in the context of spiritual growth and digging within oneself to gain insight and understanding. Finally, the image making needs to exist within the context of the real world, and have some knowledge and relationship to the ancient and modern traditions and concerns of the artist.

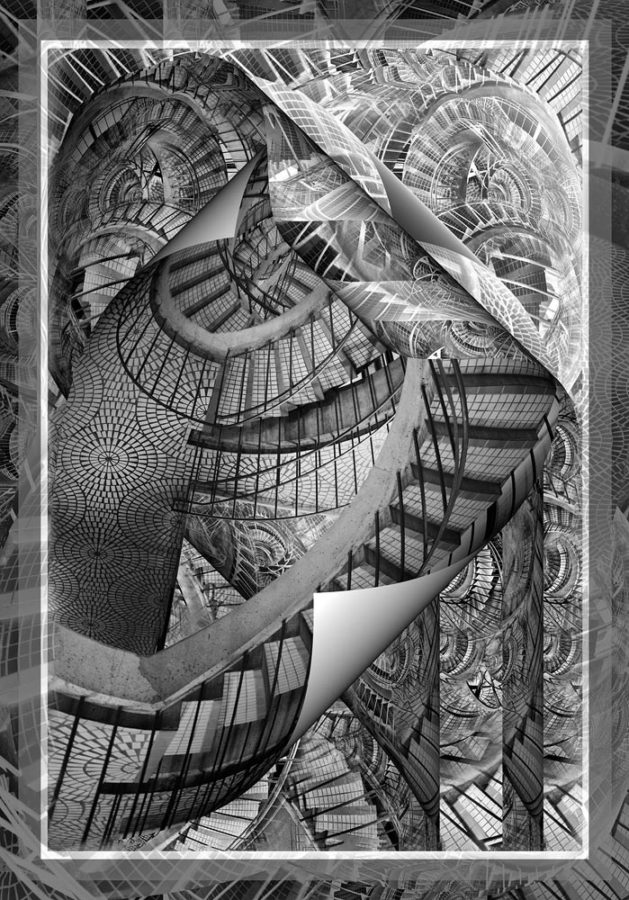

Speaking of context, my work lies at the intersections of many styles and disciplines: between east and west, classicism and modernism, photography and painting, and the new technologies of the digital era versus the handcraft traditions of the artisan. To understand my imagery, one needs to see where it fits within each of these dichotomies.

To achieve my goals, I am prepared to bring to bear the full power, scaffolding, and tricks of the trade from a number of disparate disciplines. My work uses the latest technologies and also harkens back to historic art traditions, including impressionist painting and Asian art. I am very aware of traditions of European art such as Impressionism and Expressionism, and also art traditions such as Japanese woodblock printmaking and Chinese landscape painting. When appropriate, I echo these in my work.

You may be curious: How does one become a Photographer as Poet? This, of course, is a little like the question of how one gets to Carnegie Hall. The answer, of course, is to practice, practice, practice! Everybody’s journey and story is different, but here is some of my story.

First, how did I get started with photography? How have I come to integrate photography, analog painting, a background with computers, and more into my Photographer as Poet practice?

When I was five years old, my parents gave me a box camera and I fell in love with photography. Later, I became interested in painting, and studied figurative and abstract painting at the Art Students League, Bennington College, and elsewhere. Eventually, I graduated from college with a degree in Computer Science and Math.

Following graduation from law school, I opened a photography studio in New York City at 18th Street and Broadway. During this period I exhibited at New York galleries, and had fun with the New York art and party scenes.

I supported myself largely with commercial photography assignments, with a specialization in photographing jewelry and architecture. Assignments took me many places including across the Brooks Range in Northern Alaska on foot, to the environmental disaster at Love Canal, and above the World Trade Towers, hanging out the door of a helicopter by a strap. During my years as a photographer with a studio in New York, I was privileged to get to know many of the great photographers and art directors of the analog film era.

In the 1980s, I created a number of bestselling fine-art graphics, and was the founder and chief photographer of the Wilderness Studio line of greeting cards and posters. I wrote my first book, about how to publish fine art card and posters. I also began writing commercial software and became a project-based computer programmer.

In the early 1990s, my wife and I left New York, first for a farm in Vermont, and later for the hills of Berkeley, California. We started a family. At this time I was no longer painting or photographing. I held a number of different jobs in the technology industry.

In the early 2000s I picked up a camera again and was delighted to find that I could combine my love of painting with my love of photography by starting with digital captures and using digital painting techniques to enhance my imagery in post-production.

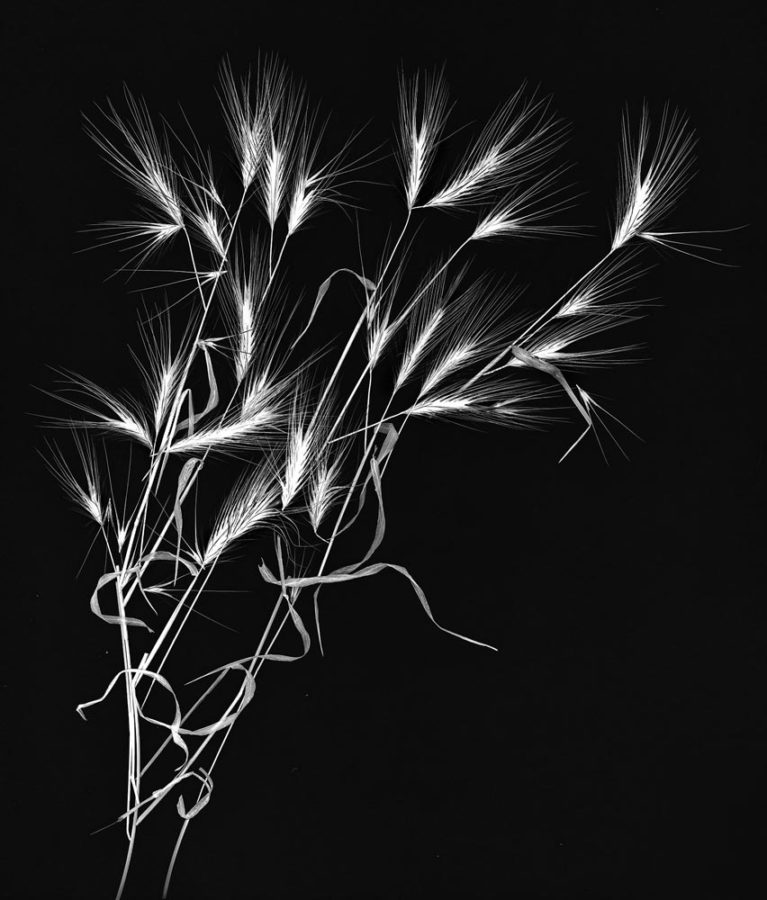

As my experience with digital photography blossomed, I experimented with and developed various post-production strategies and technologies. I pioneered several widely admired techniques, involving photographing flowers for transparency on a light box, multi-RAW processing, and extending dynamic range in post-production via hand-HDR.

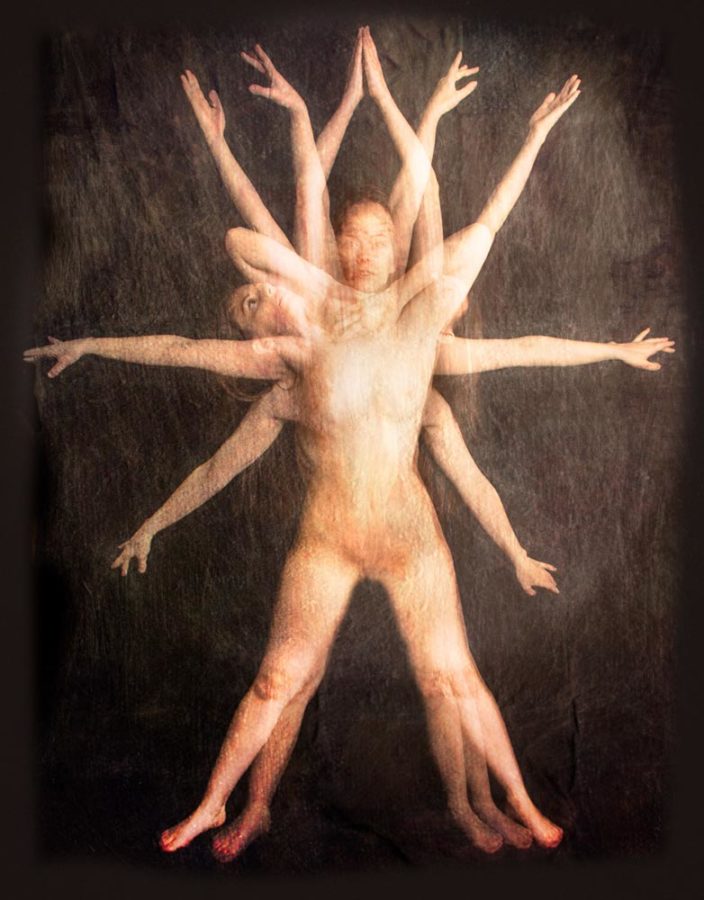

I also worked to adopt in-camera digital multiple exposures to studio photography using synchronized studio strobes.

One area of my particular interest is extreme color post-production techniques using LAB color, an alternative way of thinking about and interacting with color. In recent years, I have also collaborated with a professional radiologist on a new set of techniques to create fusion x-rays—images that combine x-ray captures with photography to show both the inside and the outside of subjects such as flowers.

In summary, as I said towards the beginning of this blog story, no knowledge is wasted. To become a Photographer as Poet requires leading an interesting life, both in terms of external opportunities for photography, and in creating and experiencing a rich internal life.

Everyone’s path is different. Your journey will not be my journey. I’ve been lucky in that my many eclectic interests and experiences have come together for me. But I hope I’ve made the case that being a photographer necessarily means sharing oneself; and that therefore the road to the highest and deepest forms of photography involve treating the work with respect, listening to one’s inner voice, and striving to be the best one can to be as a Photographer as Poet.

Viewed as poetry, some photographs are quiet and soft, like snow falling early in the morning, a simple, old-fashioned tool, or a wooden bench in a garden. Other photographs and poems are bold and brassy, like reveille in the morning. I’ve primarily illustrated this blog story with comparatively “loud” images, but I respect the variety of approaches towards the ineffable, and try to create work that is outwardly simple as well as work that is obviously complex. Quaker-like esthetic holds a place in our hearts just as much as the rococo fantasies of Antoni Gaudi; the important thing is the heart.

The title of Photographer should be considered a grand honorific. It is a great privilege to be able to be an image maker. To be a real Photographer, the noise and foolishness of petty selfies and minor commercialism should be ignored, and we should focus on what really matters, whatever that is to each of us. We need to keep working, experimenting, and taking risks in our work.

Thanks for reading my story. May your journey be exciting, interesting, and with much art along the way!

Special thanks to Scott Kelby, Brad Moore, and the Scott Kelby Blog for inviting me to write this guest blog post. I really, really appreciate it.

Harold Davis is an artist, photographer, and writer. You can find more about him and his work on his website, DigitalFieldGuide.com. He is a workshop leader, a Moab Master, a Zeiss Ambassador, and the author of many books about photography, including most recently Creative Black & White, 2nd edition, from Rocky Nook. You can also keep up with him on Instagram.